From Alexander Hamilton and some of the first immigrants to modern-day immigrants, people have left their countries in search of a better life in America. These people have immigrated to the United States to fulfill some conception of an “American Dream” that was such a prevalent and hopeful word. However, as this “American Dream” was rooted in notions of American exceptionalism, as immigrants entered the workforce and political scene, the institution of race prevailed and caused legislation that would ban immigrants. In this section, I will attempt to create a timeline and analyze some of this legislation and the perspectives of the time that led to the passings of such legislation, and how this legislation has been hindering human rights; ie how legislation and rhetoric perpetuated by the United States government have led to circulating fear and indifference that have had horrible consequences on the basic human rights of immigrants.

Legislation

First-wave: late 18th and early 19th centuries

- 1790: Naturalization Act of 1790

- 1795: Naturalization Act of 1795

- 1798: Naturalization Act

- 1803: Naturalization Law of 1802

The legislation during this early period directly after the founding of the United States was largely focused on the original definitions of citizenship. It focused, as the names suggest, on defining naturalization. Naturalization describes how someone from outside of a country may gain citizenship to it. These early acts helped define a notion of citizenship, namely who was and was not a citizen.

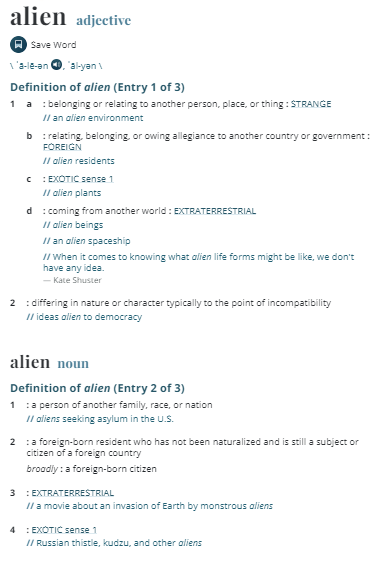

The first time in United States history that immigrants were viewed as outsiders was under the 1798 Naturalization Act, which was also the first time that the word “alien” came into legislative rhetoric. Under this act, the president was allowed to deport immigrants who were from a country at war with the United States. The word “alien” has been a large word used to describe immigrants in the late 20th century and the 21st century but actually dates back here to 1798.

This first-wave of restrictions on immigration was a precursor to the later legislative acts that would result. It set the stage for a new nation and what it meant to be a citizen in it [spoiler alert: being a white rich male helped a whole lot], in its rhetoric and precursor definitions. From these legislative acts, we can start to see how human rights restrictions for immigrants would be a challenge, as during this period, being anything other than a white rich male tended to make you a second-class citizen. Immigrants could not quite fit these definitions, so they were seen as a threat and pinned as an “alien”, something making them be perceived as not even human, let alone a United States citizen.

Second wave: post-Civil War

- 1870: Naturalization Act of 1870

- 1875: Page Act of 1875

- 1882: Chinese Exclusion Act

- 1882: Immigration Act of 1882

- 1885: Alien Contract Labor Law

- 1891: Immigration Act of 1891

- 1892: Geary Act

The second wave of immigration restrictions came after a long break. During this period, the United States was focused on wars, international and internal. It was during this period that the Fourteenth Amendment was passed, which granted citizenship to freed blacks. However, while this amendment seemed to grant equality for all, this would be far from true for both blacks and immigrants. While the Naturalization Act of 1870 extended naturalization to people of African descent, it did not allow for any other non-whites to become United States citizens. Thus, new definitions would form during this period regarding what was considered acceptable and “desirable”.

These legislative acts focused on redefining what being a “desirable” United States citizen meant. The Page Act of 1875 was the first immigration law that prohibited immigrants who were not considered “desirable”. This allowed the United States government to use immigration as a strategic tool and to pick and choose what immigrants to take. The government was against Asian immigration, shown in the direct restrictions on Asian immigrants, deemed “undesirable”, who needed to be excluded. The Chinese Exclusion Act was the first legislative act to specifically target and name a race of immigrants to exclude, while the Geary Act extended its 10-year initial timeframe. The Immigration Act of 1891 set up comprehensive laws regarding immigration and created the Bureau of Immigration. During this time, there was an increased theme of targeting “undesirable” immigrants, based on their race. In another section of this website, sociology of immigration, there will be more on this, including cartoons and depictions in newspapers of “undesirable” immigrants.

It is important to note that during this period, the United States experience can be summarized by internal expansion and Manifest Destiny. These ideals of expansion helped foster a sense of American exceptionalism and were rooted in colonialism and white supremacy. The Horatio Alger Myth was popular during this mid-19th century period and is what the concept of an “American Dream” was based on. It was rooted in the term “work hard get ahead.” Unfortunately, as the progression of time would come to show, there were other factors that determined whether or not you would be successful. For immigrants, a promise of an “American Dream” has been a huge pull factor to the United States, but unfortunately, due to these sentiments being founded on genocide, colonialism, and white supremacy, the “American Dream” was quickly shown to not be for everyone, specifically not for those who were coming to be viewed as a threat to other people’s realization of the “American Dream” – immigrants. Thus, the legislation of this time period would perpetuate rhetoric that led to immigrants being unable to obtain a fair chance of the “American Dream” and thus was a restriction on their human rights.

Third wave: pre and post World War I

- 1903: Immigration Act of 1903

- 1906: Naturalization Act of 1906

- 1907: Immigration Act of 1907

- 1907: Gentleman’s Agreement

- 1917: Immigration Act of 1917

- 1921: Emergency Quota Act

- 1922: The Cable Act of 1922

- 1924: Johnson-Reed Act

- 1924: National Origins Formula/Act

The third wave of immigration, categorized as the early 20th century, was a time of mass restrictions on immigration, marked by war and quotas. While war was the main factor causing fear after 1915 in this wave, the early part of this period was based on rhetoric.

The legislation of this period was focused on excluding immigrants by any means possible, rather than the previous legislative acts focusing on describing what would be considered “desirable” for an immigrant group. This is inherent in the characterizations of the legislative acts, which added more inadmissible groups of immigrants, created English language and literacy requirements for incoming immigrants, and revised numbers of immigrants that could enter the United States. This was known as a quota system, developed during World War 1. The sense of fear generated through war was directly linked to racism, and racism continued in a self-perpetuating cycle. Quotas continued to be based on increasing numbers of years before, eventually culminating on immigration quotas being based on the 1900 census under the Johnson-Reed Act. This itself was discriminatory as many non-European immigrant groups had not been very present in 1900 for various reasons, including Asiatic exclusion. The Johnson-Reed Act and the National Origins Act capped immigration, moved immigration back to 24 years prior, and moved the progress of immigrants’ human rights back too. The only Asiatic immigrants allowed under this emergency quota were elites – clergy or students. This redefined standards of the lowest immigrants; even the highest of society were deemed barely good enough to be “desirable” if they were that as much as they were “tolerable”.

It is also important to note some sentiments of this time and the future that stemmed from this period. The Gentleman’s agreement was an unofficial but enforced agreement between the president of the United States and the leader of Japan. It was a bilateral agreement formed that would stop Japanese immigration to the United States. This was a direct attack on Japanese immigrants and would lead to the sentiments that led to Japanese being put in internment camps during World War 2, a little over thirty-five years after the Gentleman’s Agreement would be enacted. Thus, the anti-immigration sentiments and restrictions on immigration during this time period are important to understand as one looks at United States attacks on Japanese-Americans in the 40’s. The sentiments towards the Japanese were not isolated and were running back to here and to the rhetoric that was being pushed as early as the nation was founded.

Fourth wave: The Great Depression, World War II, Cold War

- 1934: Equal Nationality Act of 1934

- 1940: Nationality Act of 1940

- 1943: Magnuson Act

- 1952: McCarran-Walter Act

- 1954: Operation Wetback

- 1965: Hart-Celler Act

The legislation during this fourth wave was a result of the tensions stemming from an America directly coming out of an economic depression, the threat of war and actual war. The acts that were enacted before World War 2 were focused on defining nationality yet again, while the post-World War 2 acts were focused on deportations and stemmed from direct hatred and fear of immigrants. The legislation further perpetuated people’s treatment of immigrants.

During international war, it is to be expected that the American government and population would feel threatened by any immigrants from countries that were not their allies. The idea of internal threats from such countries being present in the American population caused paranoia to become widespread in both the government and regular society of the United States. It is for this reason that Japanese Americans were forced into internment camps and had their rights taken away from them simply due to their race and physical appearances. Because America was at war with Japan, it only made sense to the white Americans that all Japanese were a threat to their American Dream. We can see similar sentiment today in the era of the Coronavirus as people have been very anti-Asiatic because the Coronavirus originated in China. The actions of the United States government that placed Japanese Americans in internment camps were not based solely on a perceived internal threat, however. This was due to a long standing history of exclusion and anti-immigration sentiment that can be seen as being perpetuated all the way back when the nation was founded as the term “alien” came into the discussion of immigration. White supremacy and perceived threats to American exceptionalism, thus, caused Japanese Americans to have their human rights be stripped of them as they were forced to go to internment camps and leave the lives that they had made for themselves and their stories behind. It is important to point out this restriction of human rights, as it was the greatest restriction at the time on the human rights of immigrants. The forcing of Japanese-Americans into internment camps was in itself the worst explicit barring of human rights of immigrants at its time. To learn more about this and the Japanese Americans’ stories, I suggest visiting the Densho website that I explored as a part of class.

Similar sentiments of perceived internal threats were present during the Cold War, as citizens and the government were actively seeking out communists who had infiltrated the US government. Everyone was examined, but, morally for some, it seemed easier to pin immigrants as communist, and thus “illegal” immigrants who were suspected of communism, even if they were not communist and not first-generation immigrants, would be deported. Thus, the restrictions on human rights of immigrants was as prevalent as the effects of immigration restrictions during this period, as human beings would be pitted as wrong for existing and for not being white and thus would have their rights taken away. In general, during the fourth wave, deportations became prevalent, “illegal” and “alien” immigrants continued to be detested, and thus many people’s right to have their stories heard was taken away.

Fifth wave: late 20th century

- 1982: Plyler v. Doe

- 1986: Immigration Reform and Control Act

- 1990: Immigration Act

- 1996: IIRalRA (Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigration Responsiiblity Act of 1996)

The fifth wave of immigration restrictions seemed to further rhetoric against “illegal” immigrants to the United States, specifically under the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act. This act contributed to the sentiments of anti-immigration, and it went as far as to make it a crime to hire “illegal” immigrants. As border enforcement increased, so did the actions against immigrants already in the United States.

While this wave may seem less intense than the other ones in terms of direct stripping of the human rights of immigrants, it was still a violation of their human rights because there was no major progress that turned everything around and gave them basic rights back. Instead, further legislation continued to perpetuate rhetoric and fear of “illegal” people who had “infiltrated” the United States. This rhetoric had been building since the founding of the nation, but would come into play the most in the sixth wave.

Sixth wave: Post 9/11

- 2002: Enhanced Border Security and Visa Entry Reform Act

- 2002: Homeland Security Act of 2002

- 2005: REAL ID Act

- 2010: DREAM Act

- 2012: Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals

September 11th, 2001 was a major turning point for the United States immigration policies. While things were not looking up before, this event seemed to solidify anti-immigration sentiments and was able to justify inhumane treatment of immigrants for so many. In the aftermath of 9/11, the United States government played off of people’s fears and further perpetuated them, leading to even more immigration restrictions and thus more fear.

The 2002 Enhanced Border Security and Visa Entry Reform Act added more border patrol agents and required official identification documents, and required schools to report their numbers of foreign students enrolled. The report of the numbers is directly rooted in fear and was for the sole purpose of singling out the immigrant and foreign children, causing fear and exclusion by peers. As children grow up learning that immigrants are dangerous, they continue to perpetuate the cycle of rhetoric and thus the cycle continues. The school actions were aimed at continuing this legacy and making immigrants feel unwelcome. The formation of the Department of Homeland Security was formed to have a specific part of the United States government that was set to govern internal security, and thus regulate immigration. The 2005 REAL ID Act further acted upon fears as it required ID’s to enter government buildings, restricted immigration, and enforced these restrictions by allowing the building of border protections. Despite all of this, the 2010 DREAM Act and the 2012 Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals were a step forward in the human rights of immigrants, as it worked to solidify a future for immigrant children. This era has been important in this regard because, due in part to social media, it has never been easier to spread information. Thus, pro-immigration ideas have been spreading and there have been protests, specifically regarding rhetoric and stopping legislation, to advance immigrant rights for the future.

Today, president Trump has been very explicit in his stance of wanting to bar “illegal” immigration through building a wall at the Mexican border. His perpetuation of rhetoric has furthered the anti-immigration sentiments and has led to mass restriction on the human rights of immigrants. Detention centers, ICE, and other actions have led to separation of families and forced deportations and caging of human beings. However, there has been mass resistance of his policies, in protests and art. Please view the modern times and media section to learn more about this modern day push for immigrant rights.

Summary

These legislative actions listed above are just a few examples of legislation passed by the United States government imposing restrictions on immigration. From these legislative acts, it seems to be clear to see that they are promoting the rhetoric of immigrants not being from this world. There are clear restrictions on immigrants being able to be perceived as human, and thus their human rights are restricted as they, using a modern example, are put into cages, separated from their families, and deported. This seems to me like a direct erasure on the dreams that immigrants carry as they immigrate to the United States and an end to their ability to be successful in achieving some sort of the “American Dream”. History can explain restrictions on immigration as white supremacy and race have always prevailed, and these restrictions, as seen especially today, are stripping immigrants of their basic human rights.

Importance

Today, we have seen more pro-immigration movements, despite the current president’s push to “build a wall” and deport “aliens”. He has been a big step back in the immigration human rights movement, but nonetheless, immigrants keep fighting for their voices to be heard. Alexandria Ocasio Cortez, a congresswoman, has been using her voice to push the idea that is seen on so many protest signs that “no human being is illegal”. I hope that as we progress, especially after the coronavirus, that we can truly see this and how immigrants make our communities richer and are just as deserving as rich, white, male citizens. They are not “aliens” from another planet, but rather human beings like the rest of us. They came to the United States with dreams, and we owe it to them to help them reach their potential.

Photos

Learn more

Important vocabulary, courtesy of the Merriam Webster Dictionary:

Alien

Illegal

Naturalization

Quota

To explore more on this legislation, please view the following sources, which I used in crafting this page:

(n.d. nps.gov. Accessed April 11, 2020.)

- Legislation from 1790 – 1900

- Legislation from 1901-1940

- Legislation from 1941-1960

- Legislation from 1961-1980

- Legislation from 1981-1996

Please visit the rest of the website to learn more, and to view some analysis of immigrants and their narratives and explore why it is important to be careful in rhetoric and what you participate in.